K.N. Raj’s Impact as an Economist and Teacher. Part 2.

Alumni of the Centre for Development Studies, India, recall the contributions of K.N. Raj on his birth centennary

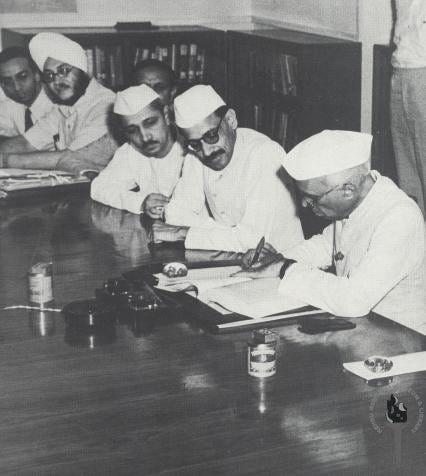

(Photo: K.N.Raj, at extreme left, and members of the Planning Commission with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, right, 1950. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.)

May 24, 2024 and May 18, 2024

May 13, 2024, marked the 100th birth centenary of Kakkadan Nandanath (K.N.) Raj. As an economist, he played a key role in India's post-independence economic development. He was an advisor to several Indian Prime Ministers, including Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and P.V. Narasimha Rao.

At the age of 26, Raj helped draft India's first Five Year Plan (1951 to 1956), including writing the introductory chapter. While serving on the Planning Commission of India, Raj and his colleagues prepared a 20-year perspective of increasing the rate of savings, among Indian households, from 5% in 1950 to 20 per cent by 1971. In 2004, Raj told The Frontline that by the target year 1971 India had "superbly met its (savings) projections".

Raj was a professor of economics at Delhi University for 18 years and was among those who founded the Delhi School of Economics. He earned his Ph.D. from the London School of Economics and a BA from Madras Christian College, Chennai, India.

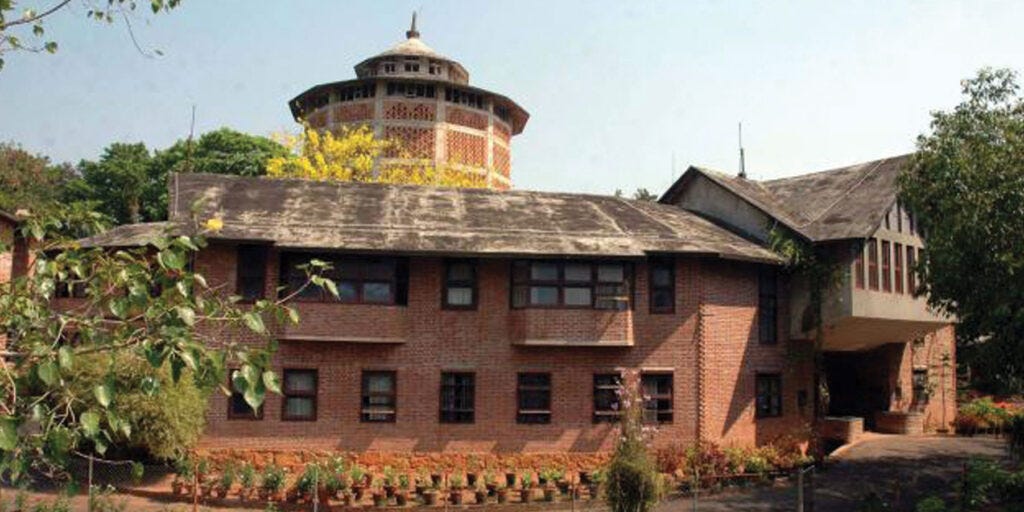

In 1971, upon returning to his home state of Kerala, he founded the Centre for Development Studies in Thiruvananthapuram. CDS, as it is known, focused on an “empirical study of different aspects of Kerala and India’s economy” employing applied economics and social science research.

Professor Raj passed away on February 10, 2010. CDS will host a conference and other events to celebrate Raj’s centennial, October 19 to 22, 2024.

Former students recall what Raj meant to them while they were at CDS, from economics and teaching insights to help with their research. This is a random collection gathered quickly over the past ten days by Cherian Samuel and Ignatius Chithelen from fellow CDS alumni with whom they remain in contact.

Contributors this week are A.V. Jose, C. Rammanohar Reddy, Cherian Samuel, Jeemol Unni, Mihir Shah, P.K. Michael Tharakan, P.S. Vijayshankar, Rakesh Basant, and Ignatius Chithelen. In the first part, published last week, the contributors were Arvind Sardana, N. Chandra Mohan, Nagaraj Rayaprolu, and Sunil Mani.

A Ringside Seat to the Founding of the Centre for Development Studies

By A.V. Jose*

In July 1971, I knocked on K.N. Raj's door at his home in Thiruvananthapuram, seeking admission to the PhD program at CDS, the new research institute he had just initiated. My classmate Usha Ramachandran, later Thorat, advised me to do this after our final exams at the Delhi School of Economics.

When Sarasamma, Raj’s wife, opened the door, she ushered me onto a new road. As a research assistant to Raj, I got a ringside view of the founding of India's finest institution for studying applied economics. The key ingredient was Raj’s assemblage of a unique group of highly talented faculty members. Together, they moulded CDS into a renowned institution for nurturing skilled professionals in economics and the social sciences.

Raj trimmed my rough edges and nudged me to work on important issues such as wages paid to agricultural labourers in India. Early on, while preparing a research paper on wages, he re-wrote the entire text and recommended it for publication as a CDS working paper. His rule was simple: if you had an idea with a story around it and had collected enough data as evidence, he would rewrite, enhance, and shape the story into a paper worthy of publication. The senior faculty at CDS followed the same rule after I drafted a chapter on wage trends for the celebrated CDS/United Nations study on Poverty, Unemployment and Development Policy in 1975.

Raj agreed to supervise my Ph D thesis, “Agricultural Labour in Kerala, A Historical and Statistical Analysis”, on the condition that I submit it to Kerala University and not to Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi, with which CDS was affiliated. However, I found it challenging to cope with his demanding standards.

In 1978, fate came to my rescue when Raj went on a year-long assignment to prepare a new work program for the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Bangkok, Thailand. N. Krishnaji, a senior faculty member at CDS, helped me improve my thesis. Upon his return in 1979, Raj carefully read my dissertation and approved its submission only after making me mend the loose ends that still remained.

In addition, I was a direct beneficiary of his path-breaking work for the ILO. In May 1980, after submitting my thesis, I was hired by the ILO Asian Employment Program in Bangkok due to Raj's recommendation for the post.

Over the next three decades, I kept in touch with Raj and the CDS community, which helped me stay rooted in India. This enabled me to return to Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, after my retirement from the ILO in 2008.

By then, Raj's health was already deteriorating. The loving care of his sons Gopal and Deena, with dedicated support from Hari and Vasantha, kept him cheerful right to the end. I was privileged to join Gopal and Deena as they consigned Raj's ashes to the Indian Ocean. The same ocean, near CDS, keeps reminding me of Professor Raj's calm, depth, bounty, and occasional fury.

May, 24, 2024

*A.V. Jose earned his PhD from CDS in 1980. A retired official of the International Labor Office in Geneva, he is based in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. He is a visiting fellow at both CDS and the Gulati Institute of Finance and Taxation. He is currently revising his PhD thesis for publication, expecting to finish before K.N. Raj’s centenary year ends.

(Photo: Lecture halls and tower, housing library, Centre For Development Studies, India. Architect Laurie Baker. This and following photos courtesy CDS.)

K.N. Raj Sought to Help Improve India’s Economy and Not a Comfortable Academic Tenure in the West

By C. Rammanohar Reddy*

The late very bright Sakti Prasad Padhi and I were among the last PhD students of Professor KN Raj. We began working with him at the Centre for Development Studies in 1979/1980. Our misfortune was that while we were Raj’s PhD students, we were never taught by him in the classroom, and missed out on what we used to be told were his legendary powers of exposition and the ability to excite the minds of the young.

Still, it was a unique experience to be Raj’s PhD student. He was the one who pointed me in the direction of my research—on the variations in the incidence of agricultural labour across India – and introduced me to Surendra J Patel, a longstanding friend of his, who in the late 1940s had done the early research in this field.

The topic was very much part of Raj’s larger interest over decades about how land and labour worked in rural India, from the colonial era to the present. He gave me the freedom to work at my pace and let me take different directions; only very gently pulling me back from blind alleys and nudging me in different directions. He was generous with his time too. There never were these “Office Hours” as is now common practice among university professors, a practice that constrains student-teacher interaction. You could walk into his room at any time, provided he was not in a meeting.

Raj made it possible for me and my fellow students to travel much more than was possible on our travel budgets under the PhD scholarship (Rs 1500 a year I think it was) and organized projects in the field so that we did not have to live within our scholarship of Rs 400 a month (of course 1980 prices!)

My tragedy was that by the time I completed my thesis in the late 1980s, Raj, while still possessing his brilliant mind, was often in poor health and could not read an 80-100,000-word thesis at one go. It was a sign of being free from the shackles of prestige and procedure that he agreed that another brilliant colleague of his, Professor N. Krishnaji, who was then at the Centre For Studies In Social Sciences, Kolkata, would read my draft and inform Raj of whether or not it would pass muster.

All this was a very different experience from what we had been (wrongly) warned of, that Raj was a taskmaster and that we’d be lucky to have our thesis passed.

We were students of Raj but our experience with him was much larger. His sense of perfection meant that he never did publish the magnum opus on India’s agrarian structure thar he had worked on for decades. But the ideas had already been put out in various papers in the late 1960s and early 1970s. And many of those were the seeds of work that another generation of brilliant economists such as Professors Krishna Bharadwaj and Amit Bhaduri carried forward in their pathbreaking work on land, labour, credit and produce in rural India.

KN Raj was an intellectual giant and a towering personality, who built/helmed many institutions. It was inevitable that there used to be strong differences of opinion with colleagues and even students (as for example when he was the Vice Chancellor of Delhi University) and Raj was not always in the right. All that does not matter. Raj was first and foremost an academic who was imbued with a sense of purpose, of using his knowledge to participate in nation building. Not for him awards, positions, or comfortable tenure in the West, which were all there for the picking. He was an economist who sought to understand the Indian economy so that we could make India a better country.

*C. Rammanohar Reddy earned his MPhil, 1980, and PhD, 1988, from CDS. He then worked as a journalist at the Deccan Herald, Bangalore, and The Hindu, in Chennai and Hyderabad, and later as Editor of the Economic and Political Weekly, Mumbai. Now residing in Hyderabad, he is the founder-editor of The India Forum.

(Laurie Baker, architect of CDS campus, left, with K.N. Raj, center)

CDS Should Set Up a Project to Study K.N. Raj’s Contributions

By Cherian Samuel*

My 1982 MPhil batch enrolled at CDS about a decade after its founding in 1971. I came across academics and students, from different Indian states and with varied backgrounds and interests, which was a testament to the vision of Dr K.N. Raj in setting up the Center.

Like others in my batch, I had the privilege of attending Dr Raj’s lectures on the Indian economy, which offered insights into his wide ranging and significant scholarship.

We also enjoyed the fruits of his stature as an influential economist in Independent India since he was able to attract leading academics and policymakers to speak at CDS. I remember, for instance, a talk by P.S. Appu, who was then Bihar’s Chief Secretary, head of the state’s administration. He was a friend of Dr. Raj. Appu outlined the “resource curse” development challenge faced by Bihar.

At a personal level, Dr Raj was key to helping me find data for my MPhil thesis on Industrial Sickness in India, with a focus on West Bengal. I got access to the data, during a visit to Kolkata, only because of a letter from Dr. Raj. The letter introduced me to Dr Hiten Bhaya, a former member of India’s Planning Commission, who was then the Director of the Indian Institute of Management, Kolkata. Dr. Bhaya’s warm welcome and kind hospitality to an MPhil student like me was emblematic of the goodwill and respect that Dr Raj enjoyed among Indian policymakers of his generation.

As we reflect on Dr Raj’s legacy, I am grateful for his providing the gift of CDS to the state of Kerala and its people. A great public good, in my view. As a Kerala emigrant living in the US, visiting CDS and meeting friends on the faculty, as well as students, has been part of my trips to India. As we celebrate his birth centenary and remember him, CDS should consider establishing a research project focused on Dr Raj’s contributions.

Cherian Samuel earned his M Phil from CDS, 1982-85, and Ph D from University of Maryland (College Park), 1995. He is a former Staff member of the World Bank Group.

(Laurie Baker, architect of CDS campus, left, with K.N. Raj, center)

(Image: K.N. Raj’s note approving Jeemol Unni’s thesis, July 1981.)

K.N. Raj’s Note Approving My Thesis Is A Cherished Medal

By Jeemol Unni*

I joined CDS as an MPhil student in September 1979. We were a small batch following the very illustrious senior batch who later turned ‘Maharathis’ in the fields of academics, journalism and policy making. It took some time before the professors at CDS started taking us seriously. In the mean time we enjoyed ourselves and the company of our illustrious seniors.

My stint at CDS led to my love for data, which continues till today. Browsing through volumes of data in the basement of the CDS library, where the Census volumes and other data sources were lodged, became my hobby in the afternoons when I was free. Imagine my surprise when I first encountered Professor Raj also browsing through volumes of data and other material in the basement. My encounters with him were often in this basement.

Professor Raj was an enigma and most of the students were afraid of him. He would join the students and other faculty in the CDS canteen for lunch. It was a bit scary to find oneself seated next to him. One never knew what question he would shoot at you. Fortunately, we were always reading something in Economics, another hobby I developed, so I had an answer to his question ‘what are you reading these days?’ The next question was the difficult one, ‘tell me what you learned from it?’ Whew!

The most difficult decision was when we had to choose our supervisor/advisor for the MPhil dissertation. Professor Raj had the least number of MPhil and PhD students who successfully completed their dissertation with him. And amazingly I am one of them! I think he became my advisor by a process of elimination! I would have meetings with him to decide on the topic of my thesis. Those were truly scary. He would espouse a large number of hypotheses and theories in one sitting. He was reflecting on his theory of commercialization of agriculture, I think! I would rush back to my room and try to write down what I understood and remembered. I often think that if the students and faculty around him had taken up any of these themes for research they would have made amazing academic careers.

I finally chose a simple idea from my observation of Kerala’s agricultural fields since my childhood. The declining cultivation of rice paddy and the conversion of paddy lands to plantation crops, banana and coconut. Amazingly Professor Raj was happy with my idea and got me access to the Cost of Cultivation data at the Kerala University’s Agro Economic Research Center. I industriously copied all the data and conducted an analysis using electronic calculators, with the help of Professor Chandan Mukherjee. There were no computers and laptops in those days.

I delivered the first hand written draft of my MPhil thesis to Professor Raj with trepidation. Within a few days he called me and I went with fear written all over my face. He said “this is fine. I have edited the first chapter of the thesis. I know you are capable of editing the rest, so just edit the rest yourself.” I was startled. I went back to the hostel room and wept for two days. I was sure that this was his way of rejecting my thesis.

At the end of two days Rakesh Basant, my batch mate and future husband, said “Just do what he said. He probably really meant it.” So, I sat down, read his edited chapter and attempted to edit the rest of the chapters. Again, I delivered my hand written chapters to him with fear. In a few days he called me and returned my draft and said, “It’s Ok, get it typed”. I could not believe my ears. He wrote a letter stating the same, which he pinned on to the thesis. I have preserved it and wear it like a medal!

And so went my encounters with the legend Professor K.N. Raj!

In later years, when we visited CDS, he was losing his memory. But he never failed to recognize me or the topic of my MPhil thesis! In loving memory of Professor Raj.

*Jeemol Unni earned her MPhil from CDS, 1979-1981. She earned a PhD from Gujarat University. She is a professor in economics at Ahmedabad University. Earlier, she was the Director and Reserve Bank of India Chair Professor at the Institute of Rural Management, Anand, Gujarat.)

K N Raj’s Economic Insights Are More Relevant Fifty Years Later

By Mihir Shah*

It is a remarkable tribute to K N Raj’s body of work, as also his deep understanding of the Indian economy and society, that so much of what he wrote, taught, and advocated continues to have abiding relevance more than half a century later.

Raj always pleaded for greater humility among the practitioners of economics. He was concerned about the trend towards narrowness of vision and concerns in the economics profession in the 20th century. In a November 1976 CDS Working Paper titled “Village India and its Political Economy,” Raj argued persuasively for a more transdisciplinary approach, alive to the questions of power in society. At the same time, he emphasized the need to factor in the specifics of the context, while applying theoretical frameworks developed in very different socio-historical contexts, not only across nations but also within a country as diverse as India. Raj was acutely aware that if we continue to ignore the crucial role played by caste relations in village India, economic theory would keep providing us misleading answers and policies.

At this time of near universal support for the re-privatization of government owned banks, it would be a singular service for us to listen to Raj’s iconoclastic voice of wisdom, since he played a key role in providing the intellectual case for the nationalization of banks in 1969. Raj showed that rural credit is not merely a commodity that the poor need to free them from usurious moneylenders, it is also a public good, critical to the development of a backward agrarian economy like India. Raj found that mere legislation and control had not led to an “optimal allocation of investible resources.” Therefore, Raj concluded that the nationalization of large banks was the only way forward.

Raj had also anticipated the serious issues that have emerged regarding lending by government owned banks, which call for several reforms. The policy of “social coercion” adopted after bank nationalization has achieved only limited success. In particular, the dependence on usurious rural moneylenders has increased, following the strict application of profitability norms to the banks in 1991. However, there has been significant progress in many parts of India in resolving the trade-off between access to affordable credit and banking profitability during the past 20 years, through the democratization of formal credit, by linking women’s self-help groups (SHGs) with bank funding. As a result, inexpensive credit is now available to the poorest sections of rural India because the extraordinary repayment record of SHGs has reduced transaction costs and improved profitability of the banks. But this has been possible only due to the remarkable expansion of the outreach of the government owned banks into the remotest corners of rural India.

Reading Raj again has been a salutary reminder of where economics as an academic discipline has gone, but where it really needs to go. I am not making an argument against rigor or parsimony, both of which are redeeming features of any scientific discipline. But, as Raj warned, when parsimony gets placed at such a high pedestal that it begins to lose touch with reality and when rigor is defined in terms so narrow, it obfuscates more than it illuminates. Contrary to those who argue for value-neutrality in science, Raj has alerted us to the need to ground economics on a sound ethical footing.

I sincerely hope all students and teachers of economics will move forward this agenda within the transdisciplinary tradition of political economy, never taking their eyes off the gravest problems of our time, especially those afflicting the people and causes without a voice, which were always the ones closest to K.N. Raj’s heart.

*Mihir Shah joined the MPhil program at CDS in 1978 and was directly admitted into the PhD program, which he earned 1985. He then lived and worked with the Adivasi tribals in Central India for 30 years. From 2009 to 2014, he was a member of India’s Planning Commission. Mihir is now a Distinguished Professor at Shiv Nadar University, Delhi, where he leads the MA program in Rural Management.

An Accidental Student of K.N. Raj

By P.K. Michael Tharakan*

I am an accidental student of K.N. Raj. I was absent at the CDS interview for MPhil, was persuaded by my former PhD guide in history to try my luck in the area of applied economics and that too in the 'lower' class of MPhil, was nearly persuaded by the CDS faculty committee to drop the topic for my MPhil thesis on which I had set my heart and soul.

After I got to CDS, I was fascinated by Raj since he was a thinker and teacher who combined economics with history and the study of institutions. I was not only mentored by him but was also shaped by him. I had the distinction of being an MPhil and PhD student of Raj. In the end though I could not submit my PhD thesis to him for approval due to his failing health.

I also had the distinction of co-authoring Raj’s brilliant discourse on Agrarian Reforms in Kerala. I can safely say brilliant because the whole essay carries Raj's inputs alone, with mine being totally absent.

Raj deeply believed in the merits of decentralization in public administration and local governments as well as at CDS, which he helped build. I learnt almost everything on decentralization from him and in the process became an 'expert' on the subject. Kerala is deeply indebted to him for its relatively better decentralization schemes among the states in India.

I remember Raj for his courage. More than one occasion can be cited of his legendary courage and determination. A presentation on terms of trade in Indian industry and agriculture, by Professor I.G. Patel, Director of the London School of Economics (1984-1990), was publicly attacked by some influential Indian politicians. Raj supported Patel.

One morning Raj rushed into my room laughing uncontrollably. He showed me a letter from the Speaker of the Lok Sabha, India’s parliament, demanding that Raj explain why he supported Patel. I thought it was a serious matter and said so, provoking further laughter from Raj. He said he was waiting for a chance like this so that he can get the attention of the Indian public to a subject like terms of trade. "They can do whatever they like to me. I do not care"; was his comment. That in essence was Professor K.N. Raj.

*P.K.Michael Tharakan earned his M Phil and PhD from CDS. He was the Chairperson of the Kerala Council for Historical Research; Vice Chancellor of Kannur University, Kerala; Chair in Decentralization and Governance, ISEC, Bangalore; and Director, Kerala Institute of Local Administration, Thrissur.

(Photo: K.N.Raj, left, with K.R. Narayanan, former President of India.)

K.N. Raj Emphasized the Importance of Studying Regional Economic Issues

By P.S. Vijayshankar*

I first heard of Dr. KN Raj in 1980, when I read a paper written by him in the journal Seminar. It was surprising because it stood in stark contrast to many doomsday predictions about an imminent collapse of the Indian economy in those post-Emergency (1975-77) days. Later, as I got to know more about the work of KN Raj, I realised that such out-of-the-box thinking was quite characteristic of him. Though he was thoroughly trained in conventional economic theory, Raj developed a deep distrust about the capacity of theoretical models drawn from elsewhere in understanding the complexities of a backward agrarian economy like India. He crafted an empirical method of compiling and examining available data and evidence and infusing fresh thinking into theory. He also was instrumental in setting up new systems for data collection. Centre for Development Studies (CDS), which Raj set up in Thiruvananthapuram in 1971 is an embodiment of this vision of its founder.

I joined CDS as an MPhil student in the batch of 1982-83. At a personal level, entering CDS as a student at an age of 22 was a remarkable event in my life. For students like us coming from rural colleges affiliated to universities in Kerala, CDS opened up a whole new world. At CDS, I was fortunate to attend the brilliant lectures by Dr Raj on the macroeconomic framework for the Indian economy, which involved the study of land, labour, credit and commodity markets and their linkages. This was the substantial content of the book that he promised to write but never actually wrote. After CDS, when I moved to Madhya Pradesh in Central India, I got a closer view of “village India and its political economy”. I saw moneylenders charging usurious rates of interest while controlling several markets simultaneously. Raj ascribed this phenomenon to the monopoly power enjoyed by the asset-owning classes in the rural areas.

Raj’s classes combined economic theory with deep analytical insights drawn from empirical work, deriving new conclusions. I remember that he would thoroughly prepare for his lectures with detailed lecture notes and sections from original readings. He always encouraged students to consult original writings of authors and constantly investigate their insights in the light of empirical evidence. The methodological emphasis of the training at CDS on data and empirical orientation of research stayed with me for life. Though Raj did not discredit theory, he persuaded us to remain agnostic about theoretical frameworks. His emphasis was more on keeping an open mind about the dynamic reality around us and to be able to perceive and respond to change. Having lived in a rural area in a backward agrarian economy for over three decades, I see the relevance of this core insight of Raj. It has helped me every time I have tried to approach and study rural India through the lens of economics.

The study on “Poverty, Unemployment and Development Policy,” conducted in 1975 by Raj and his CDS colleagues, brought the “Kerala Model” to the forefront of development policy discussions. The important point here seems to be that, after independence, state governments in India followed their own development trajectories, giving rise to many models based on these experiences. My own study of the past 75 years of policies in Madhya Pradesh bring out many such regional stories.

It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say that the influences of KN Raj as an economist and teacher and CDS as an institution have been generation-shaping ones.

*P.S. Vijayshankar earned an MPhil at CDS, 1982 batch. He then moved to Madhya Pradesh where in 1990 he co-founded the non-profit Samaj Pragati Sahayog. He lived and worked with tribals in Narmada valley for over 30 years. Currently, he is a Professor of Practice at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Shiv Nadar University, Rural Management Program.

K.N. Raj Asked Students to Use Analytical Reasoning to Answer the Right Research Questions

By Rakesh Basant*

I joined CDS as an MPhil student in September 1979 and found the Centre to be intellectually very vibrant. For a person like me who had come from a relatively less rigorous academic environment at Rajasthan University, Jaipur, the change was quite dramatic in terms of learning experience.

After a few weeks at the Centre, I realized that the vibrancy in the academic culture was almost entirely due to senior faculty members like Professor Raj. I saw him every day in the library, reading or collecting data from various reports. He knew the thesis topics of all students.

Since faculty members joined students for lunch at the CDS canteen, I had daily opportunities to chat with the faculty. Raj showed a keen interest in my thesis even though Professor A. Vaidyanthan (Vaidy) was my adviser.

Raj would ask probing questions on my ongoing research for my MPhil thesis. He would suggest books and articles to read and asked my opinion on readings he mentioned during our last conversation. Initially, I was nervous about sharing my views. But, after a few such conversations, I realized that Raj wanted students to reflect and analyze the content rather than just finish reading a book or article. It was perfectly fine with him if my analysis was sketchy and not well articulated.

On days when I was unable to read the books and articles he suggested, I would avoid going to the library or the canteen at the time Raj usually ate lunch!

The second thing that I imbibed through my conversations with Raj and other senior faculty at CDS was that, to write a good thesis, it was very important to ask and seek answers to the right questions. A solid analytical argument based on good empirical analysis was critical for an analysis. One should neither ask frivolous questions or get carried away by very sophisticated analytical techniques. In fact, I do not know of any other economist, besides Raj, who was able to use simple cross-tabulations to provide valuable insights on key complex questions.

My high point at CDS was the day when Raj and Vaidy invited me to Raj's home. Over bottles of chilled beer and salted peanuts, they tried to persuade me to stay on at CDS, after my MPhil, to pursue a PhD. Unfortunately, due to personal reasons, I was unable to accept their offer, thereby losing out on the opportunity to learn more from Raj. As luck would have it, I wrote the final draft of my PhD thesis at CDS as my adviser Professor K.K. Subrahmanian had moved to CDS from the Sardar Patel Institute of Economic and Social Research, Ahmedabad, where I had registered for my PhD.

Now, I am retired after thirty years on the faculty at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad. Looking back, I am convinced that I would have been less of a teacher and researcher if I was not exposed to the CDS culture which Raj so painstakingly and lovingly built.

*Rakesh Basant earned his MPhil from CDS, class of 1979. He taught economics at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, with a focus on innovation and public policy, entrepreneurship and business strategy.

(K.N. Raj, right, in London while studying at the London School of Economics.)

K.N. Raj’s Vision of Combining Economics With Other Disciplines to Analyze Development Issues

By Ignatius Chithelen*

I did not understand much of what Professor K.N. Raj covered in his three lectures on macro-economics, at the start of my batch of 15 MPhil students at CDS in September 1981. This was not surprising since earlier I had studied politics, MA, and philosophy, BA.

I am grateful to Raj though for setting up CDS which admitted students like me, with no prior study of economics, for its MPhil and PhD programs in applied economics. At that time, and likely today, no other academic institution in India allowed students to pursue advanced degrees in disciplines in which they had no prior degrees.

Following a conversation after one of his classes, Raj lent me a slim book. The author argued, with extensive empirical citations, that the French Revolution of 1789 was not a class struggle as portrayed by leftist researchers and ideologues. The revolution, the author pointed out, was the culmination of protests over food shortages, taxes, and other grievances of the citizens.

Insights from the book further enhanced my interest in basing analytical conclusions on empirical data. However, I did not record the name of the author and title of the book. So far, despite Google searches and other efforts, I have been unable to find those details.

My MPhil thesis was on the economic origins of co-operative sugar factories in Maharashtra, India’s largest sugarcane producing state, and their pricing policies. P.K. Michael Tharakan and Chiranjib Sen were my thesis advisors. In sixteen months at CDS, I learned much about the business economics of agricultural and commodity products, the impact of politics on business policies and the relevance of studying economic and business history.

Studying for an MPhil at CDS was by far my best education. This was because of the faculty and fellow students as well as the method of grading students through papers and a thesis. Writing several drafts, together with further reading and analyses, led to a wider and deeper understanding of an issue. This was a far superior way to learn, at least for me, compared to preparing and sitting for one-shot three hour final exams.

Also, it was a big help that CDS did not charge a tuition fee and paid a fellowship which more than covered the room rent and cost of meals.

*Ignatius Chithelen earned an MPhil at CDS, 1981-82. A Chartered Financial Analyst and an investment manager, he worked at the Economic & Political Weekly, Mumbai, and Forbes, New York. He is the publisher of Global Indian Times.