Is Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water His Epic Novel

ABRAHAM VERGHESE’S NEW NOVEL, SET IN KERALA, IS LIKED BY OPRAH WINFREY BUT NOT BY THE NEW YORK TIMES

This article, first published May 5, 2023, is being re-published since Global Indian Times has also begun posting on Substack.

https://www.globalindiantimes.com/globalindiantimes/2023/5/5/abraham-verghese-covenant-of-water

May 5, 2023

Kerala is the stage for Abraham Verghese’s The Covenant of Water which was published this month. Spanning the years 1900 to 1977, the novel follows three generations of a family that suffers a peculiar affliction: in every generation, at least one person dies by drowning.

The land in the southern Indian state slopes from the Western Ghats and “meets the Arabian Sea in a latticework of lagoons and extensive backwaters…Water is the defining element of the state,” Verghese wrote in a travel article for The New York Times Magazine.

Verghese, 68-years-old, grew up in Ethiopia, where his parents migrated from Kerala to teach physics in schools. He spent his summer vacations in Kerala, visiting his grandparents. Later, while studying at the Madras Medical College, Verghese spent his breaks there.

On his overnight journey from Madras - now Chennai - to Kerala, “I’d awake at daybreak to find my train as if by magic transported to another country, another continent even, one with a lush green landscape, waterlogged paddy fields, rivers and streams, coconut palms clogging the horizon,” Verghese wrote in 2012 in The New York Times Magazine.

The abundance of water “also shapes Malayali character,” wrote Verghese last month in the New York Times. “I think it’s responsible for the fluid facial movements that allow Malayalis to convey volumes without uttering a word.” The language in Kerala is Malayalam and hence Keralites are also known as Malayalis.

Verghese is a professor and Vice Chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine at the School of Medicine at Stanford University. He is also the author of several books and his work has appeared in the New Yorker, Atlantic, The New York Times, Granta and The Wall Street Journal, among others publications.

Born in Addis Ababa, he is the second of three sons. He grew up reading books, including The Secret Seven series by the British author Enid Blyton, which was also popular among students in English language schools in India. “Books were a gateway to a world more exciting than the one I lived in,” he told The New York Times.

Verghese began his medical training in Ethiopia. After the emperor Haile Selassie was deposed in 1974, he joined his parents in the United States, working as an orderly, or nursing assistant, in a series of hospitals and nursing homes. He then earned his medical degree from Madras Medical College, India.

Like many other foreign medical graduates in the U.S., he found that only the less popular hospitals and communities would hire him. From 1980 to 1983, he worked as an internal medicine resident in Johnson City, Tennessee. He then finished a two-year fellowship at Boston University School of Medicine.

Verghese returned to Johnson City as an assistant professor of medicine. There, contrary to national projections of the AIDS epidemic, he had to care for a large number of patients with HIV, surprising for a small rural town with a population of about 70,000.

His work in Tennessee taught him the difference between healing and curing, he notes on his website. “One can be healed even when there is no cure, by which I mean a coming to terms with the illness, finding some level of peace and acceptance in such a terrible setting; this is something a physician can, if they are lucky, help facilitate.”

Verghese took time off from medicine to earn an MFA from the Iowa Writers Workshop in 1991. He then became a professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Texas Tech Health Sciences Center in El Paso, Texas, where he lived for the next 11 years.

In El Paso, he finished his first book My Own Country: A Doctor’s Story, published in 1994. In it, he described his medical experience, including as an orderly and dealing with AIDS patients. A film based on the book, My Own Country, was directed by Mira Nair for Showtime. Verghese’s second book, The Tennis Partner: A Story of Friendship and Loss (1997), explored his friend and frequent tennis partner’s losing struggle with addiction.

In 2002, Verghese became the founding director of the Center for Medical Humanities and Ethics at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. He joined Stanford University School of Medicine in 2007 as a tenured professor and senior associate chair for the Theory and Practice of Medicine.

In his writing and work, Abraham Verghese continues to emphasize the importance of bedside medicine and physical examination in an era of advanced medical technology. He contends that the patient in the bed often gets less attention than the patient data in the computer.

Verghese’s previous novel, Cutting for Stone, 2009, was set in Ethiopia. It sold over 1.5 million copies in the United States and was on the New York Times bestseller list for over two years.

Speaking about Cutting for Stone, Verghese notes on his site: “I wanted the reader to see how entering medicine was a passionate quest, a romantic pursuit, a spiritual calling, a privileged yet hazardous undertaking. It’s a view of medicine I don’t think too many young people see in the West because, frankly, in the sterile hallways of modern medical-industrial complexes, where physicians and nurses are hunkered down behind computer monitors, and patients are whisked off here and there for all manner of tests, that side of medicine gets lost.”

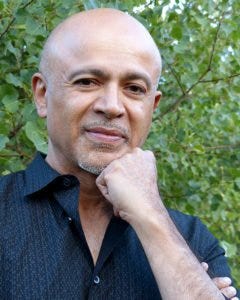

Photo: Abraham Verghese

Verghese is from a family of Syrian Christians. Their ancestors were converted to the faith by the apostle St. Thomas, who traveled to Kerala in the first century A.D.

Verghese is a non-believer. Yet, during one of his trips to Kerala, he visited the Parumala Church in his father’s hometown of Mannar, Kerala. Saint Gregorios, the first saint of the Syrian Christian church who died in 1902, was buried there.

Christians and Hindus pray at the church seeking favors or visit to give thanks for favors received. “The rough spot I had gone through a year ago made me take a vow for all our sakes, but particularly for my youngest son, that I would visit the saint’s tomb,” Verghese wrote in 2012 in The New York Times. His third son is from his second marrriage.

The family in Verghese’s new novel The Covenant of Water are also Syrian Christians like Verghese. The book, which runs into 736 pages, has received mix reviews.

“It is one of the best books I’ve read in my entire life. It’s epic. It’s transformative…It was unputdownable!,” wrote the actor and TV host Oprah Winfrey in OprahDaily.com. She also selected the book for her book club, 2023.

Oprah is perhaps the most influential voice in the U.S. media today, with her endorsement sharply boosting sales of everything from chocolates and shoes to music albums and novels. Not surprising then to see this response from Verghese on Instagram: “I'm shocked, delighted, and overflowing with gratitude that @oprah chose THE COVENANT OF WATER for @oprahsbookclub. What a blessing!”

Similarly, author Joan Frank, in her review in The Washington Post, wrote that Verghese’s novel is “grandly ambitious, impassioned work…a magnificent feat.”

In contrast, Sam Sacks of The Wall Street Journal states that “Dr. Verghese’s portrayal of the medical practice is so stirringly noble that it seems even more critical to consider books by equally exacting standards…This strong, uneven novel fell short of mine, but only because it had moved me to set them so high.”

Andrew Solomon’s review in The New York Times describes The Covenant of Water as “sweeping” and “absorbing.” But he adds that it is not “endowed with subtle psychological insights, and it is devoid of humor...” Verghese, Solomon adds, caters “to a voyeuristic interest in Asia by selecting its most accessibly endearing characteristics…(the) novel recalls the curry one might get in a small American farm town: exotic by local standards, not wrong in any way, but substantially softened for the locals.”

(c) All rights reserved. Copyright under United States Laws.