Why Kerala has Higher Literacy and Better Healthcare Among Indian States

Land reforms, cash crops and modern education helped improve quality of life in Kerala says P.K. Michael Tharakan

A Global Indian Times Interview by Cherian Samuel* and Ignatius Chithelen**

January 2, 2026

TO LISTEN TO AN AUDIO VERSION CLICK ON BUTTON BELOW.

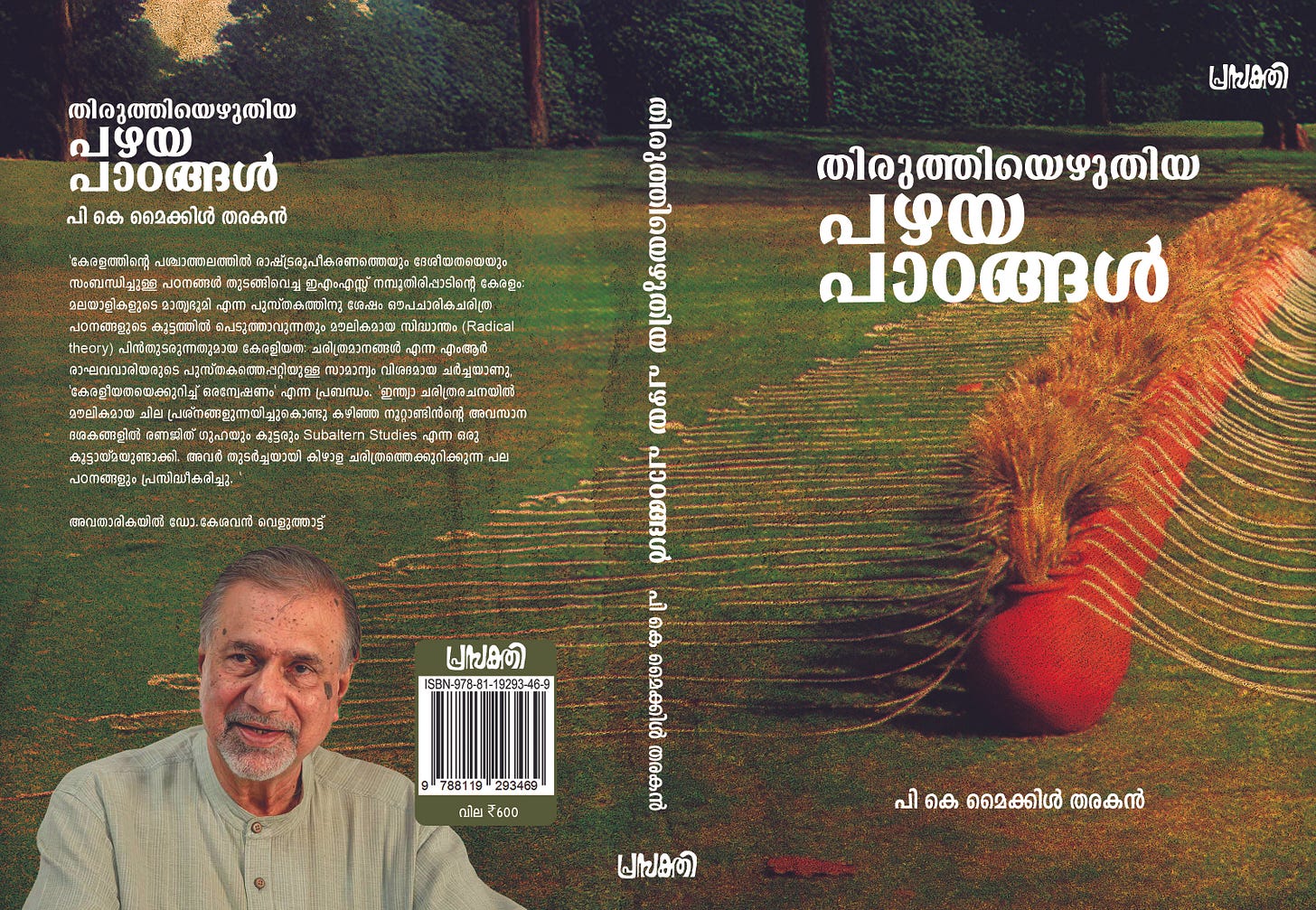

P.K. Michael Tharakan’s Thiruthi Ezhuthiya Pazhaya Padadngal (Reconsidered Old Lessons) brings together a collection of essays, in Malayalam, in which he analyze Kerala’s social and economic history, development issues, and politics.

Since 2023, he has been Chair of the Centre for Socio-economic and Environmental Studies in Kochi, Kerala. Earlier he served in several academic roles in the state: a Visiting Faculty member at the Centre since 2013; Chairman, Kerala Council for Historical Research, 2017-2023; Vice-Chancellor, Kannur University, 2009-2013; Guest Faculty, Mahatma Gandhi University, 2004-2006; Director, Kerala Institute of Local Administration, 2000-2001; Associate Fellow, 2001-2003, 1983-2000, and Research Associate, 1977-1983, at the Centre for Development Studies. From, 2007-2009, he served as a Professor and Ramakrishna Hegde Chair for Decentralisation and Governance at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. Earlier, in 1998, Tharakan was named Special Chair in Development Studies, University of Antwerp, Belgium.

Tharakan, 75-years-old, has served on numerous academic and government committees in Kerala and other parts of India. His research has been published in the Economic & Political Weekly and other journals. He has spoken at academic events around the world, including as Chairperson of the Session on Kerala at the European Conference on Modern South Asian Studies, Netherlands, 1996.

Tharakan earned a PhD in History from Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala, 1998; an MPhil from the Centre for Development Studies, 1975; and a Bachelor’s, 1972, and a Master’s, 1974, both in history, from Union Christian College, Aluva, Kerala.

In this Global India Times interview, Tharakan chats about Kerala: why the state has a high literacy rate, the role of Christian farmers and missionaries, his academic mentor Professor K.N. Raj, his family of farmers and academics, and how he ended up living on Kakkathuruthu, an island near Kochi, Kerala.

Global Indian Times: What led you to write the book?

P.K. Michael Tharakan: The book is a compilation of my old articles scattered in various publications. Credit for finding, selecting and editing them should go mainly to Prasakhthi, the publishers.

Global Indian Times: Glad it is in Malayalam.

Michael Tharakan: Yes. Writing in Malayalam was my natural choice. It is the only language I knew till my late teens. Also, my hope is that, being in Malayalam, the book will be read by a wider audience of Keralites.

(Photo: P.K. Michael Tharakan being draped in a Ponnada at the Kerala Council for Historical Research. The Ponnada is a golden shawl given as a mark of honor.)

Global Indian Times: You have been a keen student of the history of Kerala.

Michael Tharakan: There were two aspects to my work as a historian: teacher and researcher.

I appreciate the chance I got to teach, or, more correctly, discuss historical issues with students and others. These conversations were conducted in a simple and straight-forward manner. Hence, I consider myself more of a story teller than an academic teacher.

In the field of research, in the 1980s, I tried to solve a puzzle about the quality-of-life indicators in Kerala. Literacy, healthcare, and other human development indices were relatively high even though the state’s per capita income was lower than that in the other Indian states. Professor K.N.Raj asked me to study how and when this divergence began, for my PhD thesis.

I found, with what I believe is reliable evidence, that the quality of life began improving in Kerala from around the 1850s. In that decade, in Thiruvithamkoor, the Kingdom of Travancore, tenant farmers were granted proprietorship of the land they were cultivating. Within a few decades, this radical restructuring of land ownership rights also happened in the Kochi and Malabar regions of what is now Kerala.

Then, the introduction of plantation crops by European, mainly British, colonial investors, commercialized farming in the Keralam region. (Keralam is the traditional name of the region where people spoke Malayalam.) As a result, an entrepreneurial middle class of farmers emerged. These newly rich farmers, who were mainly from the middle castes, aspired for a higher social status. Pursuing a modern education, both in English and Malayalam based on a Western curriculum, became the route to prosperity as well as a higher social status. The emerging rich and middle-class farmers also sought public healthcare and other social amenities. As a result, economic, social and civil rights reform movements grew extremely strong in Keralam.

In the 1930s, the global economic depression hurt the region’s agrarian economy. This led to rising support for further reforms, mainly articulated by the left and the Indian nationalist political movements. There was a strong consensus across all parts of Keralam for a United Keralam, basic land reforms, and expansion of access to education, healthcare and other social benefits.

My research findings ran counter to the prevailing belief that Keralam’s high literacy was mainly the outcome of Monarchical benevolence and the work of Protestant Christian Missionaries. (The research was published in journals and as part of a book.)

Global Indian Times: Did the Christians play a role in raising the education levels in Kerala?

Michael Tharakan: The two major Christian denominations had different views on education. The Protestant missionaries promoted what is known as modern education, a western syllabus taught in the English language.

The Roman Catholics, both the Syrian and Latin sections, stayed away from modern education for more than a century. They viewed English as a rebel language. Only, from around 1891 onwards, inspired by their main social reform leader Nidhirickal Mani Kathanar, the Catholics grasped that modern English education was necessary for economic and social advancement.

But to give the Christians all the credit will be wrong. Government policies and demands from socio-economic and other reform movements also played a major role in the advancement of education in Keralam. For instance, the biggest increase in literacy was among the Ezhavas, a lower-middle caste, from around four percent in 1901 to nearly forty percent by 1941.

Global Indian Times: You have done research on Kerala’s plantation or commercial crops sector. What was its role in the state’s economic development?

Michael Tharakan: Initially, from the eighteenth to early twentieth century, families became rich by cultivating timber, spices, coconuts and Kayal Krishi, a type of rice paddy. They then followed the Europeans in cultivating plantation crops, notably natural rubber trees, which, along with coconut trees, are suitable for cultivation on small farms.

Some of the farmers and traders earned additional profits from processing, such as turning rubber sap into rubber sheets, milling coconut oil, weaving coir mats, and processing alcoholic toddy from the sap of coconut trees.

In the late nineteenth century, demand for Keralam’s commercial crops expanded with a rise in exports to the United States. Also, helpful was the emergence of the port of Alappuzha.

However, the farmers and traders invested only a small portion of their profits in setting up manufacturing businesses. This partly explains why Keralam still remains an industrially backward region, compared to other long-established commercial centers in India like Surat (Gujarat), Konkan (Mumbai to Mangalore), Coromandel (Chennai) and Bengal (Kolkata).

Global Indian Times: How did the Christians come to play a major role in Kerala’s plantation economy?

Michael Tharakan: A section of Christians, known as Syrian Christians, were already in Keralam before the arrival of the European missionaries. Being in the middle of the social hierarchy, they benefitted from farm ownership granted under land reforms. The Christians cultivated, processed and traded coconuts, spices and other cash crops and hence had a major role. This gave them a clear economic advantage when plantation crops were introduced by the Europeans. Some of the Christians took on loans and expanded into trading. They were also among those investing in the education and skills development of their children.

Global Indian Times: You have been a student of migration beginning with your MPhil thesis. Does the continuing migration of young people from the state concern you?

Michael Tharakan: For my thesis, I studied the migration of Christian farmers from the south to the north of Keralam, during the early 20th century.

In the southern region, either due to luck or foresight, some farmers successfully rode the cyclical swings in the prices of cash crops. They accumulated larger farms and got wealthier.

However, other farmers suffered major losses. This forced them to give up their land to moneylenders, Chitties and Kuris, as well as to fellow farmers from a similar economic and social status. Being landless, they would have had to work as laborers on plantations, maybe owned by relatives and fellow church congregants. This would bring great shame to the family in an economically stratified society.

Instead, many of the newly landless migrated to the northern Malabar region to set up farms since land was cheaper. Along with the landless, some entrepreneurial farmers from the south migrated north to buy more land and expand their commercial farming. In turn, in subsequent decades, most of the children of the migrants moved out of Keralam and India in search of better job opportunities.

Today, while lack of jobs continues to fuel migration from Keralam, I do not claim to fully understand what is happening.

(Photo: P.K. Michael Tharakan in a boat ferry to Kakkathuruthu island, near Kochi. July, 2023. © Global Indian Times.)

Global Indian Times: You were part of the first MPhil batch at the Centre for Development Studies in 1975. Professor K.N. Raj was your thesis supervisor. How did the experience shape you?

Michael Tharakan: I owe my ability to pursue research and teaching mainly to Professor Raj. I was a student from a rural area in Kerala. He may have selected me for the MPhil program because I ranked first in both the BA and MA exams at Kerala University. But he soon found that he had to teach me even the basic aspects of academic work, like how to write a footnote!

Professor Raj supervised my MPhil thesis as well as guided me on my PhD thesis. Unfortunately, he was unable to officially supervise my PhD thesis. However, he asked me to co-author one of his major research papers on land reforms in Keralam. In fact, my thesis, that, Keralam’s high level of literacy and other social achievements was due to changes in the state’s agrarian economy, is very much within Professor Raj’s frame of analysis. We also advocated that economic and social reform organizations must pressure policy makers to implement programs which benefit landless farm laborers, small farmers, women, fishing communities and other marginalized groups.

Global Indian Times: You are the Chair of the Centre for Socio-economic and Environmental Studies in Kochi. What is your vision?

Michael Tharakan: I was elected by the board to fill a gap that can never be filled (replacing the founder Professor K.K. George who passed away in 2022.) All I try to do is to help colleagues meet the high standards he set. Maintaining credibility is important in India since the validity of even basic research data is contested.

The staff have undertaken several reputed surveys and studies on the socio-economic and environmental impact of large-scale schemes and projects. They include evaluation of projects, funded by the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, which sought to improve the operations of schools, healthcare clinics, water supply, government offices and other services provided by local governments.

Global Indian Times: Your views on the current state of the history profession in India?

Michael Tharakan: I may not be the right person to make such an assessment, especially for all of India. But, in studies on Keralam and South West India, there are some scholars who are doing insightful work on maritime history, gender history, local history, and Dalit history. They include Abhilash Malayil, Muhammed Kooria, Dineshan Vadakeniyil – I am sure I missed some names and so apologize to them in advance. I wish their works are published in Malayalam and other Indian languages, in addition to English, so they reach a wider population, including students.

At the same time, there are some frighteningly unscientific and fake information and analysis being propagated as history in academic circles. Such works have to be countered by credible scholarship, expanding archives and using technological innovations to expand research in anthropology, archaeology and cartography.

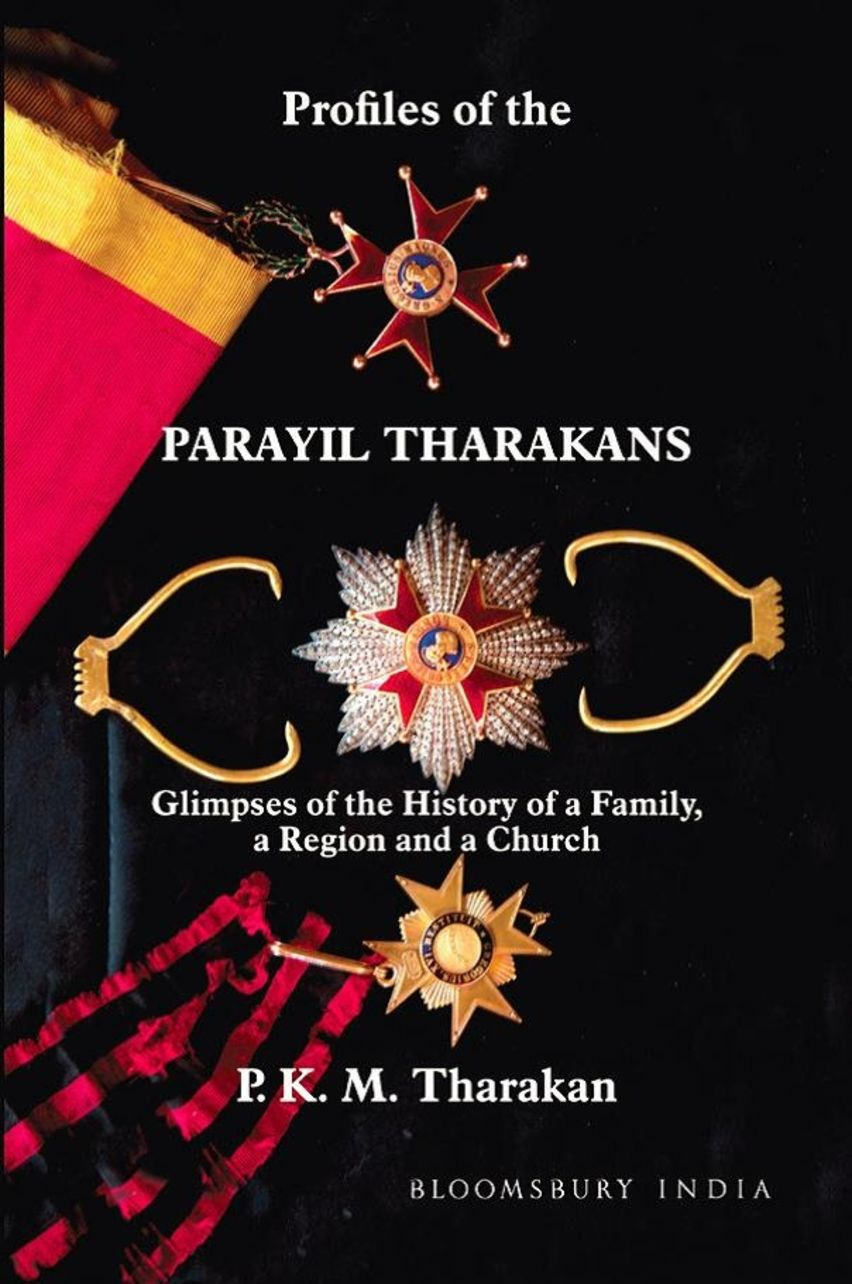

Global Indian Times: Your older brother, Professor P.K. Mathew Tharakan taught at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. You helped him with his book, Profiles of the Parayil Tharakans: Glimpses of the History of a Family, a Region and a Church. What did you two find out about your ancestors?

Michael Tharakan: I worked as a research assistant on the book. One of my tasks was to collect and interpret records kept on ola, dried palm leaves, and in other old documents. I was able to do this because of my knowledge of Malayalam and study of historical documents.

My ancestors were successful commercial farmers, particularly of coconuts, from the eighteenth to the early twentieth century. They became relatively wealthy from the rising global demand for coconuts, coir, spices, timber and rubber.

Though Christians, my ancestors were subject to caste and sub-caste social stratification. They joined others, from similar middle levels of the social and economic hierarchy, to push for reforms. They said that their tax and other financial contributions to the region’s treasury were far higher than that of the upper castes. As the book points out, some of my ancestors became renowned for their role in shaping the social and cultural history of Keralam.

Global Indian Times: You live on Kakkathuruthu, an island rated by National Geographic as one of the top ten places to watch a sunset. How did you choose to live there?

Michael Tharakan: Professor Sophie Jose-Tharakan, my life’s partner, and I inherited land on the island. Twenty-two years ago, I took voluntary retirement to join her pursuit of organic farming on the island. We built a house and moved there – well before the National Geographic coverage. (Sophie passed away in 2024.)

We were happy the magazine chose our Island as a place with one of the best sunset views. But I hope the attention also helps improve the living conditions of most people on the Island.

*Cherian Samuel, a writer based in Washington DC, retired from the World Bank. He earned a PhD in economics from the University of Maryland and an MPhil from the Centre For Development Studies, India.

**Ignatius Chithelen, publisher of Global Indian Times, is author of Six Degrees of Education and Passage from India to America. He earned an MPhil from the Centre For Development Studies, India, with P.K. Michael Tharakan and Chiranjib Sen as thesis supervisors.

For weekly Global Indian Times stories kindly subscribe. Easiest way is to email us stating Subscribe at: gitimescontact@gmail.com

TO LISTEN TO PODCASTS ON YOUTUBE OF SOME PAST GLOBAL INDIAN TIMES STORIES: CLICK ON THIS LINK.