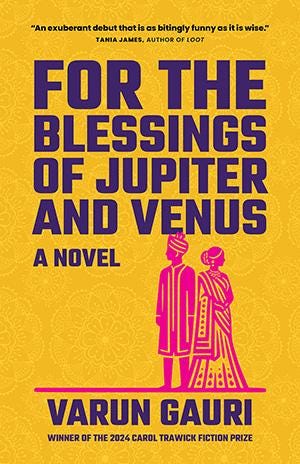

From World Bank Researcher to Writing a Novel About an Arranged Marriage

Varun Gauri speaks about development research as well as arranged marriages, the plot for his first novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus

February 14, 2025

A Global Indian Times Interview By Cherian Samuel*

Varun Gauri’s first novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus, was published four months ago. It explores the issue of arranged marriages, which remains common in India, in a modern context. Meena, a well-educated, widely traveled woman from India, marries Avinash (Avi), a politician, living in a small town in Ohio. Set in both Ohio and New Delhi, the story navigates traditional Indian customs and contemporary American culture, including racism. It examines the themes of love, commitment, tradition, and modernity, within a framework of an arranged marriage.

Since 2020, Gauri, 59, is a Lecturer in the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, New Jersey. Earlier, for nearly 24 years, he was an economist in the World Bank’s research department, Washington DC, 1996-2020. He founded and headed the bank’s behavioral science unit. Gauri was co-director of the World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior.

Gauri was a Summer Writer-in-Residence at Washington DC’s The Inner Loop, in 2023. His publications include Courting Social Justice: Judicial Enforcement of Social and Economic Rights in the Developing World, 2009, and School Choice in Chile, 1999, and many academic articles in leading journals, including papers on the Indian judiciary.

Gauri lives with his family in Bethesda, Maryland. He was born in India, moved with his family to the U.S., and was raised in the American Midwest. He earned a PhD in Public Policy from Princeton University, 1996, and a BA in Philosophy from the University of Chicago, 1988.

In this Global Indian Times interview, Varun Gauri chats with Cherian Samuel about arranged marriages, conducting research in behavioral economics and writing fiction.

Global Indian Times: Congratulations on your first novel, For the Blessings of Jupiter and Venus. How did you choose the theme of arranged marriage?

Varun Gauri: Thank you for your interest and kind words.

My parents had an arranged marriage in Delhi. I was raised in America, but my parents wanted me to have an arranged marriage, too. That prospect, or its shadow, crept into my consciousness. I started to feel that romantic love is a craze, or a sickness, a view I found support for in Romeo and Juliet and Dante's La Vita Nuova. And, for me, love was sometimes a fraught, out-of-control experience, kind of uncomfortable. I didn't trust anyone to make a choice on my behalf on a subject as significant as marriage, though I guess if I'd known someone like that, I might have let them.

At the same time, my novel is as much about love as about arranged marriage. Both of my protagonists, Meena and Avi, have experience with romance and yet choose something else entirely. Meena, cosmopolitan and disillusioned by a previously failed relationship, turns to the wisdom of her late father, who advised her that “sooner or later, every marriage becomes an arrangement.” She finds a good-enough prospect: Avi, an Ohio-based politician grounded in tradition and family.

In the end, the characters find that there isn’t a huge difference between arranged marriage and love marriage. A couple needs to find their way with one another, however they meet. The main question is whether love precedes marriage or grows within it. One line from Meena’s father is, “An arranged marriage is an attitude toward time.”

Often, people feel most themselves when they fall in love. But even in love marriages, there are many influences at play—your upbringing, psychology, genetics, and nowadays even algorithms doing the matching. So romance is not entirely about your own self, either, though it feels as though it is.

GIT: Your personal journey. Where did you grow up? Interest in sports?

Gauri: My parents are Punjabi. My father’s family, originally from Multan, Pakistan, migrated to India during the partition of British India in 1947. My parents met in Delhi, and I was born in Ludhiana, Punjab. When I was two years old, my father accepted an opportunity to pursue a degree in library science at the University of Minnesota, moving the family from India to the USA. It was during the Minnesota winter, a shock!

We moved around the American Midwest during my childhood - Kalamazoo, Cleveland, Detroit. I played baseball, basketball, and ran track and cross country as a kid. Now I enjoy tennis, bicycling, travel, music, reading, and a bit of gardening.

GIT: What were the early influences that led you to research and academia?

Gauri: I loved heavenly bodies – stars, constellations, planets, galaxies -- as a little kid. In high school, I was planning to become an astrophysicist. I had a chance to meet one of my heroes, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, who developed the theory of black holes, at a research lab, while I was at the University of Chicago.

But eventually, I decided to major in philosophy and literature because I couldn’t stop thinking about ethical and moral questions. I ended up focusing on the question of why we need heroes, and whether the classical heroes are good for us. The texts I focused on in college were The Odyssey, The Mahabharata, Paradise Lost, Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morals, Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, and Kant’s Grounding for the Metaphysics of Morals.

(Photo: Varun Gauri.)

GIT: Why study public policy?

Gauri: If I really wanted to appease my parents, I would have been a doctor! I didn’t choose medicine or engineering, but my parents had heard of the World Bank, so that was good. If I’d followed my passions after college, I might have studied the history of religions or something like that, but the humanities were considered a little weird in my family. I definitely have a political passion and wanted to make the world a better place, which is why I got into development economics. I chose development because I was always interested in global fairness and wanted to do something for India, which I used to think of as my home country.

GIT: You were the Co-Director of the World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society, and Behavior. What was the motivation for the report – assume it was the first such report.

Gauri: We wanted to update mainstream views of development economics and development policy in the light of recent research in psychology and behavioral economics. The key insight was this: People do not respond directly to incentives but to those incentives as represented in their minds.

Every policy relies on explicit or implicit assumptions about how people make choices. Those assumptions typically rest on an idealized model of how people think - full information, full rationality, utility maximization - rather than an understanding of how people actually think and behave during everyday decisions.

The report argued that a more realistic account of decision-making and behavior would make development policy more effective. It emphasized “the three marks of everyday thinking.” In everyday thinking, people use intuitive, automatic thinking much more than careful analysis. They employ concepts and tools that prior experience in their cultural world has made familiar. And social emotions and social norms motivate much of what they do.

These insights together explain the extraordinary persistence of some social practices, and rapid change in others. They also offer new targets for development policy. A richer understanding of why people save, use preventive health care, work hard, learn, and conserve energy provides a basis for innovative and inexpensive interventions.

GIT: You also founded and headed the World Bank’s behavioral science unit. Why? How was the experience?

Gauri: It was a terrific opportunity to innovate, and to build what was essentially a start-up in a large organization. There are now hundreds of “nudge units” in public sector organizations, NGOs, and private sector entities around the world. It was exciting to work at one of the first in the global development space, and to use concepts like prospect theory, descriptive social norms, and stereotype threat to improve tax payments, women’s labor force participation, and household savings in low-and middle-income countries around the world.

GIT: How did you become interested in behavioral economics? How has it affected your own approach to life and work?

Gauri: I’d always been interested in the uses and limits of economics. My PhD dissertation addressed how social identities affected educational outcomes in the world’s closest national approximation to Milton Friedman’s school voucher system, in Chile. Eventually, I saw, like that character in Voltaire’s Candide who realizes he’s always been speaking “prose” without knowing the word for it, that I’d long been struggling to interpret economics through a more psychological and social lens. It was a thrill to finally discover the papers of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky (Kahneman won a Nobel Prize in Economics, 2002, for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science.)

GIT: You left the World Bank Group to teach at Princeton? Why?

Gauri: I was ready to step outside the bureaucracy. I’d always wanted to teach and was excited to work with the next generation of development economists and practitioners.

GIT: What are your current research projects?

Gauri: I’m interested in global distributive justice. With colleagues at the Norwegian School of Economics, I am working on a large-scale lab experiment that tests the Rawlsian view of society as a system of fair cooperation. In particular, we investigate whether the experience of working together generates moral obligations to help the people one has cooperated with.

GIT: You have now written your first novel. Writing a novel is entirely different from writing a research paper. How did you manage the switch?

Gauri: I’ve long been interested in literature. I started the first pages of my novel more than twenty years ago. I would write a handful of pages, put them down for months or years, re-read my writing and decide it was all crap, start over with another handful of pages, and repeat. This went on until I started to attend fiction writing workshops, particularly one sponsored by the Virginia Quarterly Review in Charlottesville, which gave me the ear, skills, and confidence to finish a novel. I really dove into my novel, finishing two complete drafts, during the covid pandemic.

GIT: Who are your favorite novelists? Any of them influenced your style of fiction writing?

Gauri: Kazuo Ishiguro, JM Coetzee, Elizabeth Harrower, Chinua Achebe, George Eliot, Leo Tolstoy, Margaret Atwood, Hang Kang, Tessa Hadley, Orhan Pamuk. I wish I could say my style resembled any of theirs!

GIT: Do you have links to India? Do you travel there?

Gauri: I had several research projects, over the years, in India. I was particularly interested in the judiciary and the impact of Public Interest Litigation. Now I travel for personal reasons. Last spring, I had a wonderful time in Jodhpur attending my cousin’s wedding.

GIT: In your novel, Avinash faces racist attacks as an Indian politician in Ohio. This is in contrast to the portrayal, in the popular media in India, that Indians in the U.S. are a chosen minority, including tech billionaires and surgeons, who face no racism. Your view?

Gauri: Avi is running for office in a small town. Although he’s interested in issues of ordinary governance – public safety and local economic development – his backers pursue a Hindutva-inspired agenda. They want this little town to place diya candles in front of the town hall on Diwali and for the schools to recognize Hindu holidays. Local agricultural elites, the mainstream whites of European descent who have dominated this little town for decades, fear they are being replaced. They go on the offensive, making fun of and campaigning against Avi’s arranged marriage, which offends their sensibilities. Indians in America don’t encounter a lot of racism as long as they “stay in their lanes” as individuals, as high-achieving professionals in urban or semi-urban areas, and do not mobilize as a community.

GIT: Is there another novel in the offing?

Gauri: I have a short story set on a university campus. The themes I’m interested in are related to the first novel: authenticity, characters trying to figure out who they really are. Authenticity is becoming increasingly more complicated in the world of AI: What is a real essay, a personal thought? What do I believe for myself as opposed to what an algorithm points me towards?

My story is set in the near future, not when cyborgs are controlling us but when we may have more AI assistance in making decisions. This is going to result in some clarity and some confusion for a while. We’ll need to think through the personal and social consequences of some of the choices we’re making.

*Cherian Samuel, a writer based in Washington DC, retired from the World Bank. He earned a PhD in economics from the University of Maryland.

To SUBSCRIBE to Global Indian Times, send email address to: gitimescontact@gmail.com

Chamkila and Amarjyot’s duet ‘Rondi Kurlondi nu ve koi le chalia muklave’ describes two lovers lamenting their separation as he witnesses her being whisked away by her new husband, a stranger to whom she has been married off by her parents in an arranged marriage, possibly without her consent.

There are several layers to the lyrics which provide an insight into the cultural attitudes, expectations and norms as they relate to women in such communities. An english translation here available here: https://anotherdabblingdilettante.substack.com/p/chamkila