Eight of Ten Institutes With Highest Retractions of Scientific Research are in India

Studies show work of some scientists and research institutes in India is of very poor quality says Ashok Nag

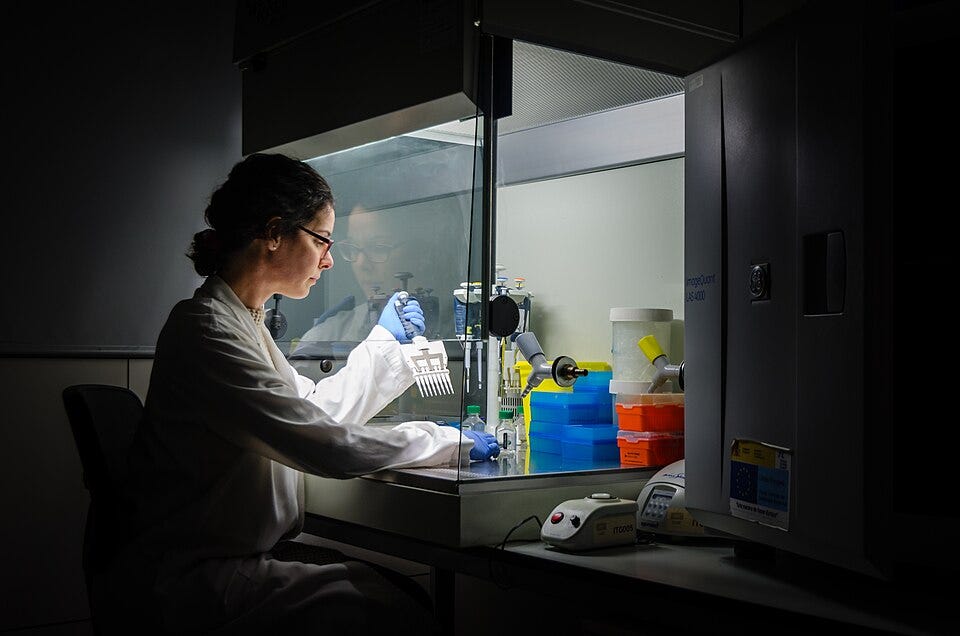

(Photo: Science researcher. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.)

August 1, 2025

By Ashok K. Nag*

Scientists do not have to swear to maintain the honor of their profession, unlike physicians who have to take the Hippocratic Oath. But they expect fellow scientists to pursue knowledge without cheating and other unethical actions. In the quest to monitor and promote ethical research practices by scientists, a couple of studies have made a valuable contributionn by examining two key indicators of misconduct: document retractions and publications in delisted journals.

In recent years, especially since 2020. there has been a sharp rise in the retraction of published scientific documents. More than 65,000 documents were retracted over the past 25 years, half of them during the past five years, according to the Retraction Watch Database. Research articles, conference papers, clinical studies, review articles and meta-analysis account for nearly all of the documents which were retracted.

A fifth of the documents were retracted due to questions about the validity of the data used. Fake peer reviews and limited or no information each accounted for a tenth of the retractions. While scientists in China account for a fifth of the retracted documents, those from India are a close second. Researchers in the United States account for about 15%.

The retraction of a published document signifies substantial doubts about the integrity of the study’s findings, the validity of its methodology, or the reliability of its conclusions, often due to serious breaches of research ethics. Such misconduct includes plagiarism, data fabrication or falsification, copying the work of others with only superficial modifications, manipulation of the peer review process, and unauthorized re-use of data or information.

In the case of published research articles, a retraction does not mean its removal from the journal’s website or other repositories. However, retracted articles must be clearly identified as such in the article itself and across all digital platforms and bibliographic databases, as per guidelines of the Center for Scientific Integrity. In some cases, the authors themselves initiate the retractionsm upon the discovery of unintentional errors. This voluntary retraction is the honorable course of action.

The Retraction Watch Database was established by the Center for Scientific Integrity in 2018. In 2023, the not-for-profit organization Crossref acquired the database and made it publicly accessible.

High retraction rates imply that there was little or no supervision of the quality of work at the institutions where the scientists conducted their research. This aspect, of the overall quality of work at an academic or research institute, is examined by Lokman I. Meho, a Professor and Librarian at the American University, Beirut.

Using data from 2022-2023, Meho analyzed the risk of research misconduct and compromise of integrity at an institute, as indicated by the level of retraction of documents by their scientists. The analysis, known after its creator Meho, covered 1,500 institutions in 82 countries and included 12,813 retracted documents.

Meho found that eight out of the ten institutes with the highest retractions were based in India. Overall, of the 21 institutions around the world with very high rates of retraction, 13 were from India, four from Saudi Arabia, and one each from China, Bangladesh, Iraq, and Jordan.

For his analysis, Meho developed an index to evaluate unethical practices, within research institutions across various countries, based on seven bibliometric indicators. Prominent among these indicators are the retraction rate of documents, publications in delisted journals, and hyper-prolific authorship. Meho uses data from reputable sources including SciVal, InCites, Elsevier, Scopus, Web of Science, Medline, and Retraction Watch. He describes his method in a research article entitled “Gaming the Metrics? Bibliometric Anomalies and the Integrity Crisis in Global University Rankings,” May 2025.

(Image: bust of Plato. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.)

Both the Retraction Watch Database and Meho’s data rely on analysis of research articles indexed in a reputed and searchable bibliographic index. Coined in 1969 by Alan Pritchard, the term “Bibliometrics” refers to “the application of mathematical and statistical methods to books and other media of communication.” Bibliometrics encompasses methods that allow scholars to quantify publication patterns, author productivity, citation networks, and the overall structure of scientific knowledge.

Such indexing is also a key part of tabulating author citations and enhancing a journal’s credibility. Leading indexing services include Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar.

The need for bibliometrics emerged due to the sharp rise in scientific research, following World War 11. The catastrophic deployment of the atomic bomb, during the war, revealed that future conflicts would be determined less by the might of a country’s conventional military forces and more by the research and innovation pursued to develop nuclear and other advanced weapon systems. Consequently, governments, which had the funds, sharply increased their funding for nuclear and advanced science and technology research and development. This in turn led to rising volumes of research documents and the need to index them.

One of the indexes, the Science Citation Index (SCI), is a major quantitative tool to assess a researcher’s influence by the frequency and spread of citations of their work. The index is a database which tracks citations of scientific papers. The SCI was created in 1960 by Eugene Garfield, who founded the Institute for Scientific Information. He was a pioneer in the efforts to measure the research impact and individual productivity of scientists. Garfield started his career as a librarian at the Welch Medical Library at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, U.S.

Currently, the process of retraction of documents and delisting of journals is mainly supervised by committees composed of researchers. These initiatives have been instrumental in upholding a reasonable standard of trustworthiness among scientists.

The reliance on standardized metrics to capture scholarly impact provides both opportunities and challenges. Citation counts and research impact factors can provide objective measures to assess the work of a scientist. In fact, such measures are widely used by academic and research institutes to help make decisions about the hiring, funding, and promotion of staff. Not surprisingly, some scientists view the metrics more as targets to be pursued, in order to advance their careers and secure funds.

It is imperative for researchers to recognize that citation counts often reflect contemporary interests and are not an absolute indication of the quality of their work. In this regard, it is worth noting that the works of Plato continue to be widely read and cited in scholarly works. This is not due to the number of citations they have accumulated over the past roughly 2,400 years. It is because of the enduring insights provided by Plato’s writings.

*Ashok Kumar Nag is a Mumbai based consultant in information management and data analysis. He spent over 25 years in the Statistics and Information Management department of the Reserve Bank of India, retiring as an adviser. Ashok earned his Ph.D. from the Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India.

This is an interesting article. However, are the universities included in the study representative of all universities in India (or in each of the other countries)? If not, the implied negative inferences about Indian universities may be misleading.