Why Emperor Akbar’s Church in Agra Shows India's Religious Tolerance

Emperor Akbar’s Church and the Red Taj in Agra are historical reminders of India’s respect for other cultures says Sunil Mani

(Photo: Akbar’s Church, Altar. November 15, 2025. © Sunil Mani.)

December 6, 2025

By Sunil Mani*

TO LISTEN TO AN AUDIO VERSION CLICK ON THE BUTTON BELOW:

Last month, my wife Dilla and I visited Agra, not to see the Taj Mahal or the Agra Fort or Fatehpur Sikri, all renowned monuments from the Mughal era, 1526 AD to 1857 AD. Instead, we went there to see two less popular sites which were also built under the rule of Mughal emperors. They whisper a different kind of history—one of religious dialogue and respect for other cultures. A Roman Catholic church, known as King Akbar’s Church, and a linked cemetery with its “Red Taj”.

My trip to Agra was both a personal and spiritual pilgrimage. In the 1940s, my father traveled from Kottayam, in Kerala in the South, to Agra, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, to pursue his intermediate studies in Agriculture at Agra University. I recall him talking about the religious and cultural significance of Akbar’s Church; he did not mention the cemetery. Also, as Christians, Dilla and I were curious to learn about the Christian community who lived, worshipped, and were laid to rest in Agra, under the rule of Moghul emperors who were of the Islamic faith.

(Photo: Akbar’s Church, interior. November 15, 2025. © Sunil Mani.)

The Mughal Emperor Akbar ruled much of North India from 1556 to 1605. Though a devout Muslim, he was renowned for his religious tolerance and his keen interest in learning and debating about the virtues and practices of other faiths. His incisive and witty exchanges with Birbal, a Hindu and one of his key advisers, are deeply embedded as folk tales in Indian culture. They also continue to be popular as stories to entertain and educate children.

In the 1580’s, Emperor Akbar invited some Portuguese Jesuit priests, who were based in Goa, India, to his court. Impressed by their learning, he asked them to translate Christian texts into Persian, the official language of the Mughal court. Also, around 1598–1600, he granted the Jesuits land near an Armenian Christian settlement in Agra and financed the construction of a small church. It was the first Roman Catholic church in the Mughal Empire and the principal Catholic place of worship in Agra, serving both European residents and local converts.

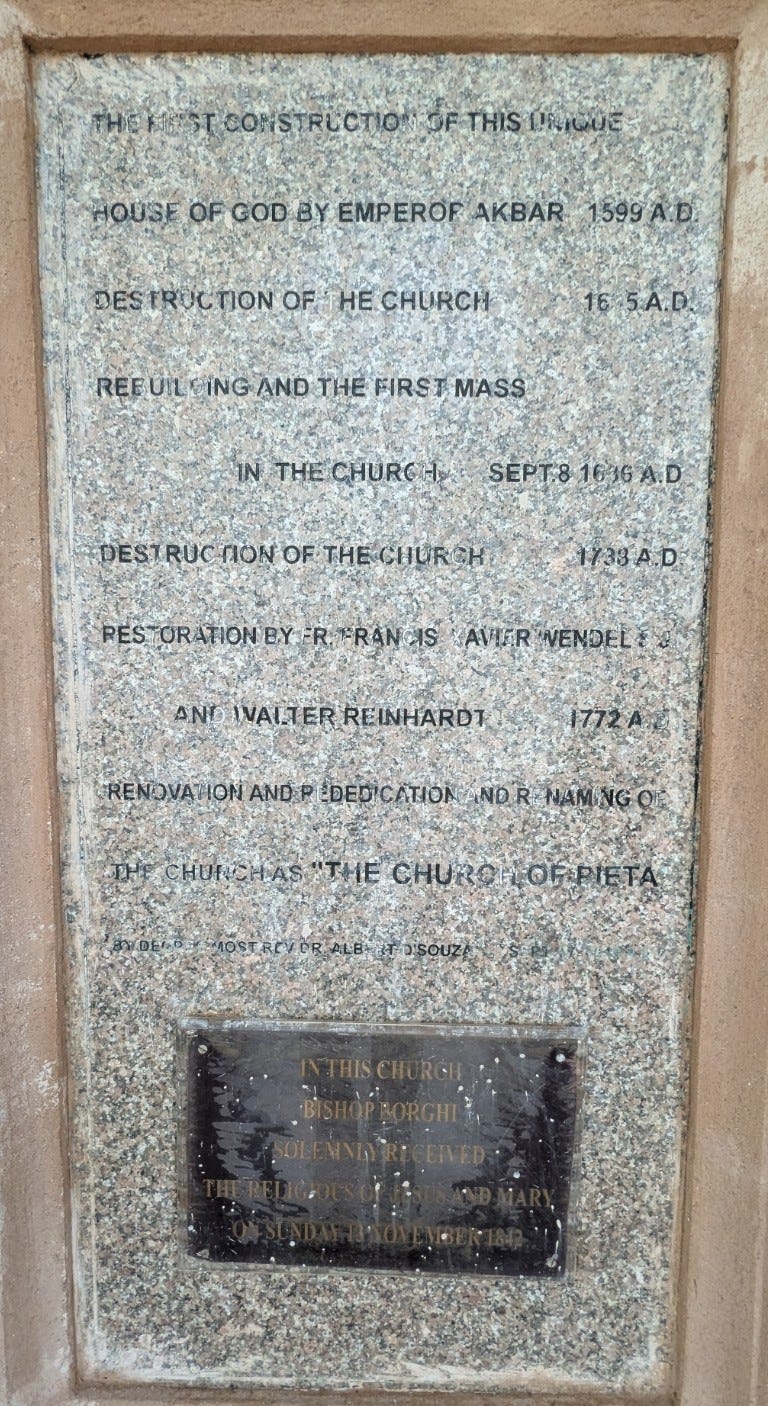

(Photo: Akbar’s Church, Plaque. © Sunil Mani.)

When we visited, the church was under repairs, covered in scaffolding. Yet, as we walked around, I reflected upon memories of my father, envisioning him praying in the church eighty years earlier. We were also connecting with a glorious period in India’s history. Dilla and I were in awe of how a modest church provides evidence of Emperor Akbar’s spirit of tolerance. As we touched the altar, we felt we were touching a moment in history when leaders of different faiths sought dialogue rather than distance and conflict.

Akbar’s son, Emperor Jahangir, continued granting funds to the church. In the early seventeenth century, the church’s stature grew more important after some members of the extended imperial Mughal family were baptised there, according to researchers. Apparently, their conversion from Islam to Christianity was approved by the emperor.

In the 1630’s, the fortunes of the Akbar Church shifted briefly under Emperor Shah Jahan, Jahangir’s son and Akbar’s grandson. In 1635, following his conflict with the Portuguese, Shah Jahan ordered the demolition of the church, reportedly bartering the release of Jesuits he had imprisoned for the destruction of the building. However, within a year, the emperor granted permission to rebuild the church, which was done by partly using materials from the demolished structure. Mass was celebrated in Akbar’s Church again in 1636.

(Photo: Red Taj, Agra. © Sunil Mani.)

In the mid-eighteenth century, the church was looted and badly damaged, following the invasion of Agra by the army of Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali. The church was restored in 1769 and architectural extensions were carried out in 1835. This transformed the structure into a layered palimpsest rather than a single Mughal-era building.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built nearby, under the direction of Joseph Anthony Borghi, then Vicar‑Apostolic of Tibet–Hindustan. He initiated the construction in 1846 and blessed the finished cathedral in 1848-9. During our visit, we attended the Sunday Mass in Hindi at the cathedral, which starts at 5 pm.

Akbar’s Church ceased to be a cathedral but continues as an active parish and heritage site of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Agra.

(Photo: Cathedral of Immaculate Conception, Agra. © Sunil Mani.)

Dilla and I then visited the old Roman ,Catholic Cemetery of Agra. The roughly fifteen minute auto-rickshaw ride, from Akbar’s Church, jolted us back into crowded, noisy modern Agra, with car and truck horns blaring and the shouts of street hawkers selling their wares. The population of the city, which is about 150 miles from Delhi, is estimated to be more than two and a half million.

The cemetery, which was set up in the seventeenth century, served as the principal burial place for generations of the church’s congregation and clergy. It contains tombs of families of European, Armenian, and Indian Catholic officers who served in the Mughal and post-Mughal administrations. Many of the graves blend European Christian symbols—crosses and Latin or Portuguese inscriptions—with Mughal features such as domes, chhatris, and cusped arches.

The dominant monument within the cemetery is the “Red Taj”, the tomb of John William Hessing (1726–1803), a Dutch adventurer and military commander. It is a striking example of the integration of Islamic and Christian architecture in India. Built in red sandstone, it is a deliberate echo of the nearby Taj Mahal. The Red Taj is a miniature reproduction of the Taj’s central dome, symmetrical layout, and corner minarets.

The Taj Mahal, which was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife Mumtaz, was fully completed in 1647, after twenty two years of construction. The mausoleum represents the zenith of Mughal imperial power. The Red Taj and Akbar’s Church, while modest structures, tell compelling stories of adaptation and endurance by a small Christian community within a dominant Islamic empire. They reveal how Europeans and local Christians were not merely transient outsiders but became embedded within the social, political, and cultural life of Mughal and post-Mughal Agra.

Today, at Akbar’s Church, the Roman Catholic Cemetery, and the Red Taj, visitors see evidence of the long history of religious tolerance and cultural exchange which once played a major role in India.

I left Agra with a greater admiration for Emperor Akbar who said: “I do not want my subjects to follow my faith; I desire only that they be faithful to their own religion and live in peace.”

*Sunil Mani is a visiting professor, Centre for Development Studies, and Ahmedabad University, both in India. The views expressed are personal.

TO LISTEN TO PODCASTS ON YOUTUBE OF SOME PAST GLOBAL INDIAN TIMES STORIES: CLICK ON THIS LINK.

For weekly Global Indian Times stories kindly subscribe. Easiest way is to email us stating Subscribe at: gitimescontact@gmail.com

The architectural palimpsest concept you mention really captures how these structures embody layered histories rather than single moments. Your personal connection through your father's studies adds a dimenson that most heritage writing misses, showing how these sites function as both historical documents and lived family memory. The detail about Shah Jahan demolishing then immediatley rebuilding the church is fascinating because it shows how political pragmatism often trumps ideology in actual governance, even in eras we simplify as religiously rigid.