Inspiring Achievements of Keralite Women in Science and Technology

Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal, Anna Modayil Mani, Thayyoor K. Radha, and Tessy Thomas made major contributions to science and technology

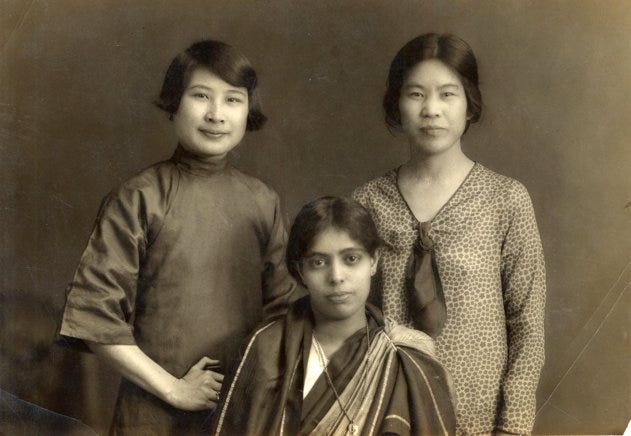

(Photo: Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal while a PhD student at the University of Michigan, around 1928. Courtesy University of Michigan.)

By Sunil Mani

Sunil Mani is a visiting professor, Centre for Development Studies, and Ahmedabad University, both in India. The views expressed are personal.

February 21, 2026

Women graduates and postgraduates in science, medicine, and mathematics account for more than 40 percent of such graduates in India. Yet, the number of women scientists in India is only about a fifth of the roughly 500,000 scientists in the country.

In Kerala, nearly half of young women are enrolled in college compared to a third of men. The state also has a higher share of women with advanced science and technology degrees than the national average. However, the proportion of Keralite women with such degrees who are in science and technology jobs is very low, similar to the national level.

Women with advanced science degrees in Kerala, as well as in India, face barriers to finding jobs in their fields. They include an inability to relocate to another city or town due to family responsibilities and expectations. Also, as with men, women prefer secure, long-term white collar jobs in government and government-run organizations.

Yet, over the past century, several Keralite women have attained major success in science and technology. They include Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal in botany, Anna Modayil Mani in meteorology, Thayyoor K. Radha in physics and computer programming, and Tessy Thomas in missiles.

(Photo: Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal, front, while a PhD student at the University of Michigan, around 1928. Courtesy University of Michigan.)

Janaki Ammal the Botanist Who Sweetened India’s Sugarcane

Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal (1897–1984) was a leading authority in plant cytology. Her work included co-authorship with Cyril Darlington, a British cytogeneticist, of the Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants, 1945, and studies of polyploidy, where an organism possesses more than two complete sets of chromosomes. The Atlas features around 100,000 plants.

Between 1934 to 1939, Ammal worked on sugarcane genetics at the Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, India. In a laboratory, she crossbred the wild Indian species Saccharum Spontaneum with sugarcane species then grown in India, to create a high-yielding strain. It also had a higher sugar content and was more suitable for the climate conditions in India. The new strain enabled India to become less reliant on sugar imports. Creating the new strain earned Ammal praise for sweetening sugarcane cultivation in India.

Some male colleagues at the Sugarcane Institute tried to block wider attention to her work, including her efforts to publish in scientific journals, because she was a woman and that from a low caste. Ammal later described the environment she faced at the institute as one of “brutal persecution” in a “pseudo-scientific” atmosphere, according to a profile of her published by Mandeep Matharu, a Herbarium Curator (Digitiser) at the Royal Horticultural Society Garden Wisley, United Kingdom.

Ammal overcame the obstacles from her colleagues in her usual way: she moved on to tackle bigger challenges. In 1939, given her global reputation, she was hired as an assistant cytologist, a scientist who studies plant cells, at the John Innes Horticultural Institute in the UK. In 1946, she became the first woman scientist to be employed by the Royal Historical Society Garden at Wisley. She earned an annual salary of £300. She also worked at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, United States.

In 1951, Ammal returned to India, at the invitation of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to reorganize the Botanical Survey of India. As a senior botanist and adviser, she focused on ethnobotany and conservation. She argued that indigenous plant diversity and traditional ecological knowledge were central to sustainable development.

Ammal then worked as chair of the Cytogenetics Department, Professor of Botany and an Emeritus Scientist at an institute in Jammu and Kashmir. During the 1970s, she played an influential scientific role in campaigns to designate Silent Valley in Palghat, Kerala, as a national park. The rain forest is full of rare orchids.

Earlier in the 1920s, Ammal worked at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, following an invitation from C. V. Raman. In 1930, Raman was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics. However, Ammal’s access to laboratory resources, mentoring and intellectual networks was restricted by upper caste male colleagues.

In 1924, Ammal secured a scholarship to study at the University of Michigan, where she earned an MS, 1925, and PhD, 1931, in botany. The title of her PhD thesis was Chromosome Studies in Nicandra Physalodes (the shoo fly plant). She was the first Indian woman to earn a PhD in botany in the US.

Earlier, she earned an undergraduate degree from Queen Mary’s College, followed by a Honor’s Degree in botany from Presidency College, both in Chennai.

Ammal was born in 1897 in a large Thiya family of modest means in Thallassery, Kerala. Her parents, who did not attend college, supported her decision to pursue a scientific career. Her father, who had a government job in the judicial service, passed on his interest in botany and science to his children. He set up a library of science books in the home. Ammal attended a local school run by Christian missionaries.

Ammal’s scientific legacy includes the sugarcane species she created. The Chromosome Atlas of Cultivated Plants (1945), she co-authored, is still used by plant breeders today. Several botanists have created flowers and plants in her honor. UK’s John Innes Institute offers postgraduate scholarships in her name to students from developing countries. Institutions in India too offer a number of scholarships in her name. In 1984, less than a year after Ammal’s passing, Silent Valley was designated a national park.

(Photo: Anna Modayil Mani, right, courtesy World Meteoroligcal Institute.)

Anna Modayil Mani the Weather Woman

Anna Modayil Mani (1918–2001) played a key role in transforming India’s weather forecasting capabilities from dependence on imported instruments to one mostly of self-reliance. As an applied scientist at the Indian Meteorological Department, New Delhi, she led teams which designed, tested and standardised more than 100 weather instruments. They included rain gauges, pyranometers, ozonesondes, anemometers and radiation sensors, specifically tailored to Indian conditions and matching international quality standards.

Mani also helped set up a nationwide network for measuring solar radiation, wind, and levels of ozone in the atmosphere. She led the research and publication of the Wind Energy Resource Survey, India, 1992, and the Handbook of Solar Radiation Data for India, 1980. These texts became essential resources for renewable energy studies and policies in India. She also documented early evidence of urbanization’s harmful impact on the chemistry of the atmosphere.

In 1964, Mani led the development of India’s first ozonesonde which enabled the precise measurement of ozone as high as 22 miles in the stratosphere. This was at a time when global concerns began emerging about the harmful effects of ultraviolet rays due to the depletion of protective layers of ozone. Her work spurred scientists in India to research the field.

In 1948, Mani joined the Meteorological Department as an applied scientist. She was not hired as a scientist because she did not earn a PhD. Despite producing substantial experimental work at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, she was denied a PhD on a technicality—her lack of a Master’s degree. Rather than feeling handicapped by her lack of a PhD, Mani immersed herself in creating instruments that could help understand and forecast weather patterns.

(Photo: Anna Modayil Mani, left, at the Raman Research Institute, 1980. Courtesy of the institute.)

In the early 1940s, Mani studied under C. V. Raman at the Indian Institute of Science. Like Ammal, she was part of Raman’s laboratory at a time when there were very few women scientists. Given strict segregation by sex, Mani and another woman student often worked in isolation. They were excluded from the wider, informal conversations which typically spread knowledge and stimulate research ideas. Some male colleagues viewed errors she made as evidence of inherent “female incompetence.”

Mani earned a degree in physics from Presidency College, Madras. She was raised in a Syrian Christian family in Travancore province, now part of Kerala, where she completed high school. Her father was an employee of the province. It is not known if her parents earned college degrees.

In 1976, Mani retired as Deputy Director General of the Meteorological Department. In 1973, she was named a honorary fellow of the Centre for Development Studies, Kerala, a role she occupied until her passing in 2001.

Anna Mani is revered as the Weather Woman of India. Her work was guided by her belief that, “Accurate measurements are the foundation of understanding nature.”

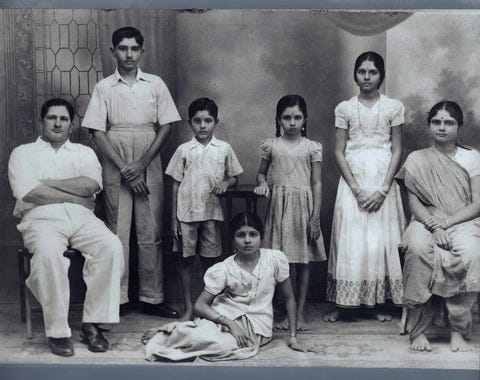

(Photo: Thayyoor K. Radha, third from right, with her parents and siblings while growing up in Kerala. Courtesy, Institute of Advanced Studies, US.)

Thayyoor K. Radha Theoretical Physicist and Computer Programmer

Thayyoor K. Radha, born 1938, researched the intersection of quantum mechanics, scattering theory and relativistic propagator structure. While none of her fourteen research papers became canonical classics, in terms of frequent citations by other researchers, they tackled advanced problems in theoretical physics.

From 1976 to 1992, Radha worked as a computer programmer, including at the physics department at the University of Alberta, Canada. She gave research ideas to some of the physicsts many of whom “listed me as a co-author on their work. There are even one or two articles that I wrote on my own,” she told Caitlin Rizzo, an archivist at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Princeton, US, in 2024.

Earlier, during the 1965-1966 academic year, she was a visiting fellow and member of the School of Mathematics/Natural Sciences at the Institute. She was invited by the director J. Robert Oppenheimer, a theoretical physicist. He led the Manhattan Project which resulted in the US building nuclear bombs. Albert Einstein was a scientist at the institute from 1933 to 1955. Recalling her experience of working at the Institute she told Rizzo, “I walked the street where Einstein lived.”

While at the institute, she presented a seminar at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada. During the visit, she met Vembu Gourishankar, a Professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering. They got married and Radha moved to Canada, where she raised a son and daughter.

Radha worked briefly as an instrutor for a course on Feynman quantum electrodynamics at the University of Alberta. She was offered an assistant professorship. But she was pregnant with her first child and “could not find a babysitter who did not smoke.” Then, since she had a difficult second pregnancy, she decided not to take up the teaching job.

Four years later, when Radha reapplied for the teaching job, the university had reduced its hiring. In 1973, she began taking courses in computer science at the University of Alberta. “I was at the top of my class. The physics department immediately sought to hire me…I was one of the only ones that knew physics and programming, so I got the job,” she told Rizzo.

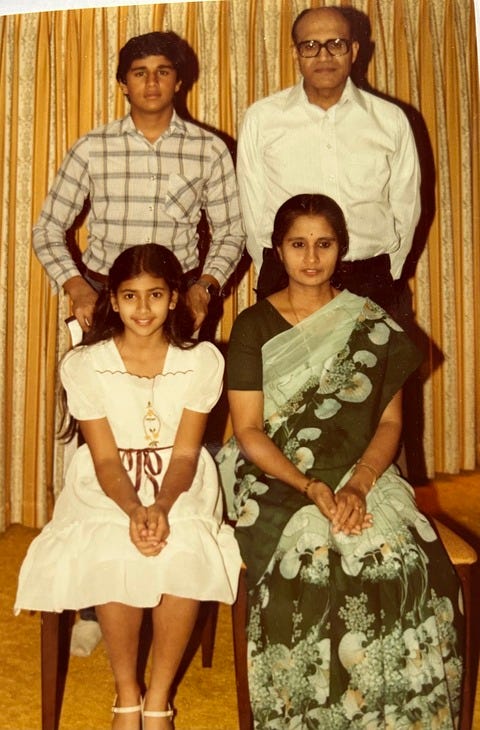

(Photo: Thayyoor K. Radha with husband Vembu Gourishankar, son Arvind, and daughter Sita. Courtesy, Institute of Advanced Studies, US.)

In the early 1960s, Radha earned a PhD in theoretical physics from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bombay. Her thesis consisted of a set of fourteen published papers, related to particle physics, Feynman propagators, and particle interactions. Earlier, she was one of four women studying theoritical physics at the University of Madras. She began college by studying mathematics and then, at the Presidency College, Chennai, she switched to studying physics. She excelled in physics, topping the class.

Radha’s mother did not want her to move to Chennai to attend college becuase “she was scared for me to be amongst men in a co-educational facility. My father convinced her to let me go,” she told Rizzo. Radha’s father, who was a schoolteacher, had also studied physics at Presidency College.

Radha, who lives in Canada, grew up in a village in Kerala which had no electricity. At night, she studied by using a kerosene lamp. She was the fourth of five children, with three sisters and a brother. After she finished high school, she told Rizzo, “my sisters were still unmarried. Rather than have a third daughter waiting to marry, they encouraged my father and mother to allow me to continue my education,”

Although she could not pursue a research career in particle physics, Radha keeps up with new advancements in the field. She also tutors university students in math and physics. Her advice to her children, grandchildren and the young, she told RIzzo, is to “pursue your passion, learn from others, and be humble. Your life will be enriched beyond your imagination.”

(Photo: Tessy Thomas, courtesy Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur.)

Tessy Thomas Managed India’s Missile Projects

While at the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), Tessy Thomas was a Project Director of Agni-IV. She led teams which integrated guidance control, re-entry, propulsion and trajectory systems for the missile, which was launched in 2014.

She was also a Project Director on the Agni-V. Last test fired in 2025, the nuclear-capable missile has a range of around 3,000 miles. In her work, Thomas was aided by her study of applied mathematics, control theory, and systems engineering.

In 2018, Thomas was appointed as the Director General, Aeronautical Systems, at DRDO. She joined the government organization in 1988 as a scientist at a laboratory in Hyderabad. Earlier she was on the faculty at the Defence Institute of Advanced Technology, Pune.

In 2014, Thomas earned a PhD in Missile Guidance from Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, Hyderabad. She earned an M.Tech in Guided Missiles from the Defence Institute in 1986; a B.Tech in Electrical Engineering from the Government Engineering College, Trichur. Kerala, and an MBA in Operations Management from the Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi, 2007.

Born in 1963, Thomas grew up in Alappuzha. Kerala, in a Christian family. Her father was an accountant. In 1976, when she was thirteen, he had a stroke and remained bedridden thereafter. Despite the financial and emotional strain, Thomas’s mother insisted she focus on her schooling and pursue her interest in science and mathematics. Her mother was a school teacher who later stayed home to raise Thomas and her siblings.

Tessy Thomas, 62 years old, is married to Saroj Kumar Patel, who was a Commodore in the Indian Navy. They have a son Tejas.

As a child, Thomas was fascinated by the rocket launches from the Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station near Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. Working as a scientist, she told the media, “I always say science has no gender. It is the knowledge and technical expertise that matters and if you are willing to learn, women can excel and succeed in this field.”

The achievements of Edavaleth Kakkat Janaki Ammal, Anna Modayil Mani, Thayyoor K. Radha, and Tessy Thomas are inspiring young women in Kerala, as well as India, to pursue careers in science and technology.

During World War II, Janaki Ammal lived in London when it was being bombed by German aircraft. In a 1940 letter to a friend at the University of Michigan, she writes, “Meanwhile we live in great danger - air raids day & night - There goes the siren- I must seek shelter. You cannot imagine the time London is having, but we are all cheerful and getting used to bombs of every description.” Ammal added, “Life isn’t worth it without a sense of danger.”